Period:

Yugoslav Wars

Region:

Estern Slavonia

The Serb victim Jovan Jakovljević - Vukovar 1991

Jovan Jakovljević (1940–1991) was the third ethnic Serb victim (the first being Stevan Inić and the second Simo Ponjević, both from the village of Bršadin) killed by members of Croatian paramilitary forces (under the command of Tomislav Merčep) in the wider Vukovar area in 1991.

Jovan Jakovljević was an honorable and upright man. He was married and had two adult sons. He was neither problematic nor ideologically radicalized. On the contrary, he was cheerful, sociable, and always willing to help others.

He was killed on the night of June 29, 1991, by a burst of automatic rifle fire at the doorstep of his home.

The Jakovljević family has remained without justice for decades. After the war, Jovan’s sons, together with other Serb residents of Vukovar, established the association “Against Oblivion” (Protiv zaborava), with the aim of shedding light on crimes and unlawful abductions of Serbs that occurred during 1991.

To date, the State Attorney’s Office of the Republic of Croatia has not issued a single indictment against members of Croatian paramilitary or police forces who are reasonably suspected of participating in or aiding the liquidation of Serbs—not only in the autumn of 1991, but also earlier, during the spring and summer, before the outbreak of armed conflict with the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA).

BACKGROUND

SFR Yugoslavia was a federal state made up of 6 republics (FR Slovenia, FR Croatia, SR Bosnia, and Herzegovina, SR Montenegro, SR Serbia, and SR Macedonia). Both Yugoslavia and the JNA were established on the principle of “brotherhood and unity” of all peoples and nationalities who lived in the SFRY.

The social and economic system of the SFRY was socialism.

The 1974 Constitution of Yugoslavia brought about the decentralization of the SFRY, which later enabled the separatist forces in Slovenia and Croatia, and later in Bosnia and Herzegovina to begin the dissolution of Yugoslavia, followed by bloody wars and persecution.

In all the constitutions of Yugoslavia, the Yugoslav People's Army was defined as the only legitimate armed force in the territory of the SFRY, and therefore, the only internationally recognized military entity. At the end of 1989, the SFRY Assembly passed amendments to the Constitution, thus replacing the one-party system with the multiparty system, which meant that besides the Alliance of Communists of Yugoslavia, other parties could now be formed.

At the end of January 1990, the Alliance of Communists of Yugoslavia collapsed, at the 14th SKY Congress in Belgrade, when sharp verbal clashes between Slovenian and Serbian delegates occurred regarding the future of the joint state of the SFRY.

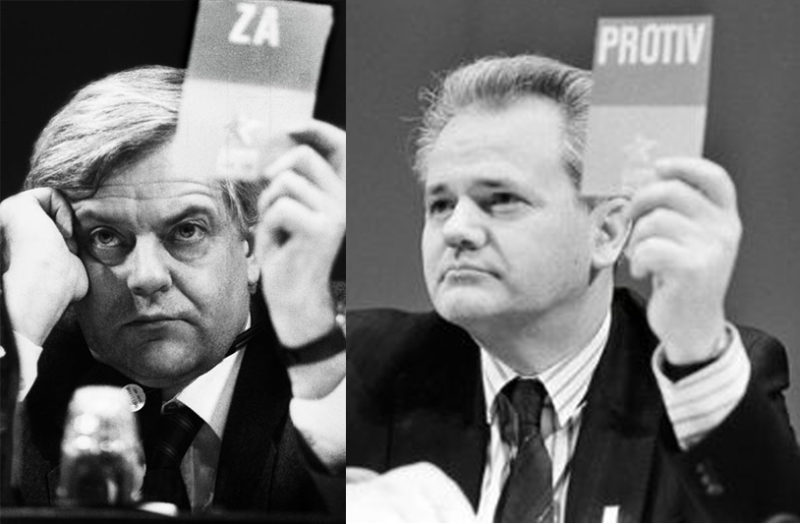

Opposing sides - Kučan and Milosević

The Slovenian delegation left the session, immediately followed by the delegation of the FR Croatia, which brought the issue of the congress into question. After them, the delegations of the FR of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the FR of Macedonia also left the congress.

Thus, after 45 years, the rule of the communists in SFRY ended.

The situation in FR Croatia

On the multi-party elections held in FR Croatia on 22 April 1990, the HDZ party won with its political program clearly stating the desire for independence and separation of FR Croatia from SFRY.

Collaborators against the Serbs: Tudjman and Račan

The victory sparked great euphoria throughout the Federal Republic of Croatia and displays of images of Ustasha criminals (Ante Pavelić, Alojzije Stepinac, Vjekoslav Luburić, and others), while Ustasha greetings and Ustasha songs could be frequently heard. This brought back memories of Serbs in SR Croatia of persecution and genocide in the Independent State of Croatia (The Nazi project between 1941-1945).

As early as spring, the HDZ and Franjo Tudjman took control of the police, the media, the prosecution and the state administration. Serbs working in the police were forced to leave in the spring of 1990 immediately after taking over the power, when the conflict at Maksimir (Zagreb's football stadium) between fans of NK Dinamo (Croatia) and FC Red Star (Serbia), were misused for anti-Serb propaganda.

Thus began a media war against everything that had to do with Serbia and Yugoslavia. In summer, the authorities of the FR Croatia in Zagreb made the decision to form the armed forces themselves. In October and November 1990, a large amount of weapons were illegally imported into the Federal Republic of Croatia for the needs of the reserve police forces, members of the HDZ and the VOC. The action was led by Martin Špegelj and Josip Boljkovac, ministers in the then government of Croatia.

Illegal arming of Croats

The JNA Counterintelligence Service made a film about this endeavor at the JNA military training polygon in Gakov in October 1990 and released it on TV Belgrade on 27 January 1991. On 22 December 1990, a "Christmas Constitution" was solemnly proclaimed in the Parliament, by which the Serbs lost their decades-old constitution rights and Croatia removed the name "socialist" in its name.

Since May 1990, the situation in FR Croatia started worsening day by day and the Serbs were terribly scared for their personal security and their property. Ustasha graffiti, slogans, posters could be seen regularly, and a large number of Serbs received threats by phone that they had to move out of their homes and go to SR Serbia. They even received threatening letters bearing the "HDZ" signature.

Violence in Zagreb at the Maksimir stadium

Even Croats who were married to Serbs received such threats.

Serbs in Croatia were fired from their jobs, and even their children were mentally and physically abused in schools. In almost all settlements where Croats had an absolute or relative majority, there were certain members of the HDZ party who had a task to keep an eye on the movement of their Serb neighbors (espionage).

The Situation in Vukovar

Vukovar is a town located at the confluence of the Vuka and Danube rivers, lying at the boundary between western Syrmia and eastern Slavonia. This boundary is a relatively recent development; until the early 20th century, the border extended further west, reaching as far as Klisa near Osijek.

The town stands at an elevation of 108 meters above sea level and has a moderately continental climate.

Traces of human civilization in this region date back to prehistoric times, particularly the Neolithic era. The area was successively inhabited by the Illyrians and Celts, followed by the Romans, who developed infrastructure such as stone roads, drained swamps, and promoted trade. In the early medieval period, South Slavs settled in the region, which in the 10th century came under strong Hungarian influence, driven by both military conflict and territorial ambitions.

Significant changes occurred in the 16th century with the arrival of the Ottoman Empire. The Turks ruled the Vukovar area for approximately 150 years. After their defeat at the Battle of Vienna, a prolonged retreat began. Vukovar was liberated from Ottoman control in 1687, at which time the town had approximately 3,000 inhabitants. A considerable number of Orthodox Serbs settled in the region during the Great Migration led by Patriarch Arsenije III Čarnojević in 1690, although a Serbian presence had existed there prior to this as well.

In the mid-18th century, a large influx of Germans and Hungarians was initiated under the orders of the Austrian statesman Eugene of Savoy and Empress Maria Theresa. The Orthodox Church of St. Nicholas was built in 1733. During the Austro-Hungarian period, Vukovar was part of the Military Frontier and served as the administrative center of Syrmia County, which stretched from Zemun to Vinkovci between the Sava and Danube rivers.

For a period, Vukovar—as well as the Baranja region—was incorporated into the Serbian Vojvodina.

Since 1840, Vukovar was integrated into the regular steamship traffic along the Danube. In 1878, it was connected to the railway network. Due to slow industrial development, population growth remained modest. On the eve of World War I, Vukovar had a population of 10,400.

During the war, many men from the Vukovar area were conscripted into the 7th Infantry Division of the 13th Croatian-Slavonian Corps and deployed to Serbia. However, a significant number of Serbs defected, unwilling to fight their compatriots. The Austro-Hungarian authorities constructed a large wooden military hospital in the village of Bršadin, known as "Wooden Vienna." Some Serbs, whom German informants labeled as politically unreliable, were interned in Austro-Hungarian camps such as Arad, Doboj, and Zenica.

Following the collapse of the Habsburg Empire in late 1918 and the formation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, Vukovar came under the administration of the Sava Banovina. In 1920, the Second Congress of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia was held there.

In 1932, Czech industrialist Jan Baťa arrived in the Vukovar region and founded a shoe factory in Borovo. He invested heavily in local development—constructing buildings, schools, churches, and sports facilities. His director, Toma Maksimović, played a key role in shaping Borovo into a modern industrial settlement.

In August 1939, the areas of Vukovar, Vinkovci, and Ilok were incorporated into the Banovina of Croatia. Protests erupted in response to the humiliating decision of the Yugoslav government under the Cvetković–Maček Agreement, although no reversal occurred. Official Belgrade hesitated to challenge the agreement, fearing repercussions from Hitler, who was already subjugating other European nations.

To ease tensions, Serbian Orthodox Patriarch Gavrilo Dožić visited the Vukovar region from November 18, 1939, for three days. His visit received extensive media coverage, highlighting the economic significance of Vukovar’s factories for the Yugoslav economy. His host was Toma Maksimović, president of the Borovo Municipality.

Following the Axis invasion of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in April 1941, the Ustaša-led Independent State of Croatia was established, and Vukovar became part of it. On the Dudik site, Ustaša forces executed nearly 500 people, predominantly Serbs. Even during the war, Croatian families from Herzegovina were settled in the region.

In 1945, the Srem Front was broken through near Vukovar by units of the Yugoslav Partisans, the Red Army, and a Bulgarian company.

There were two waves of Croatian resettlement from western Herzegovina (Grude, Posušje, Ljubuški, Široki Brijeg) and Dalmatia (Metković, Vrgorac, Opuzen, Imotski). The first wave (1942–1944) consisted of extended families relocated on Pavelić’s orders to Croatize the Danube region. The second wave (1946–1948) included widows of Ustaša soldiers who had served in the NDH’s armed forces.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Vukovar experienced significant industrial growth, attracting workers from underdeveloped parts of Yugoslavia. By the mid-1980s, Vukovar ranked second in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia by gross domestic product, just after Ljubljana.

By the end of 1989, Yugoslavia shifted from a one-party to a multi-party political system. In the 1990 spring elections, separatist forces led by Franjo Tuđman and his HDZ party emerged victorious. However, in Vukovar, the League of Communists won decisively with 65% of the vote, while the HDZ received only 26%. The Serbs did not have a national political party at the time. A Serb, Slavko Dokmanović, was appointed mayor.

According to the 1991 census, Vukovar had a population that was 37% Croat, 32% Serb, and 22% Yugoslav—most of whom were ethnically Serb. This demographic composition contributed to the disintegration of the local HDZ-led government in early 1991 and the rise of separatist forces.

In March 1991, in the village of Bogdanovci, Tomislav Merčep assembled over 2,000 Croats from the Vukovar municipality and armed them. From that moment on, the situation in Vukovar became extremely tense and precarious. The town fell under the influence of a small group of local criminals and adventurists affiliated with or close to the HDZ. They were gathered and led by Tomislav Merčep, also known as the "Slavonian Napoleon"—a man of dangerous ideas and morbid plans.

On the orders of HDZ leader and Croatian President Franjo Tuđman, Merčep was tasked with provoking war in Vukovar. The local HDZ branch compiled a list of several hundred Serbs from the Vukovar area marked for liquidation. Many of those listed were abducted and/or killed.

BIOGRAPHY

Jovan Jakovljević was born in 1940 in the village of Negoslavci, near Vukovar. His ancestors had lived in the area for over 400 years.

He was known by the nickname “Rakijica” due to his fondness for strong spirits, though he was neither an alcoholic nor a troublesome individual. On the contrary, he was known as a cheerful and sociable man, always ready to help anyone in need.

Vukovar in early 1980s

He was married and had two sons: Slobodan and Zoran. He was permanently employed as the manager of the “Sport” store, a branch of the Velepromet retail chain, which specialized in the sale of sporting firearms and was located in the center of Vukovar.

Tensions between Serbs and Croats sharply escalated across the territory of AVNOJ Croatia in early 1991, especially following the broadcast of footage from the Špegelj Affair, which revealed disturbing plans for confrontation with the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) and the Serb population. Due to the nature of his job, Jovan Jakovljević drew the attention of local members of the militant HDZ party, who devised a plan for his liquidation. Their aim was to seize his weapons stockpile, which he had hidden after realizing the risk of looting from the warehouse.

THE MURDER

On that fateful day, June 29, 1991, around noon, Jovan asked a member of the ZNG paramilitary forces what was happening.

“Jovo, you’ll find out,” the man replied.

By around 11 p.m., the Jakovljević family understood what he had meant. Jovan, his wife, and their younger son Zoran heard movement outside the house. Zoran and his mother fled to the basement. What happened next was witnessed by Jovan’s elder son, Slobodan Jakovljević, who lived in their second house, located next to his father’s.

The Jakovljević home, located in the Slavia district of Vukovar, was completely surrounded. The nearby road was also blocked to reduce the number of potential witnesses. It was foggy that night. Jovan was called to come out, with the intruders claiming to be police officers.

He replied that they could return in the morning, as it was late and he did not wish to come out. They then shouted that they would blow up the house if he refused. Realizing he had no choice, Jovan turned on the hallway light and approached the door. The door was made of oak with double glass panes. Those outside saw his silhouette and opened fire. He collapsed, falling headfirst toward the basement steps, and was killed instantly.

His murder marked the beginning of a series of killings of Serbs in Vukovar in the days that followed. It was effectively a message to the remaining Serbs in the town, warning them of what awaited them should they remain in Croatia.

|

WAR AND CRIMES IN VUKOVAR 1991

|

| CRIMES |

Killing of civilians * Karadzicevo * Kriva Bara

Nikolas Demonje Street * Kozaracka Road

Battle of Borovo Selo * Vukovar * Discrimination

|

| CRIMINALS |

Marko Babic * Mile Dedakovic * Zoran Šipoš

Martin Sabljic * Nikola Cibaric * Jure Marusic

Mira Dunatov * Ante Vranjkovic * Ivica Mazar

Vinko Leko * Vlado Lulic * Damir Sardjen * Dosen

Stipo Pole * Mante Mandic * Dujmovic * Raguz

Drazen Gazo * Tomislav Josic * Turbo vod

Blago Zadro * Tihomir Purda * Bartol Domazet

Madjarevic * Tomislav Mercep * Darko Mihaljevic

Zdenko Stefancic * Filkovic * Kolak * Prgomet

204th brigade * Gnezdo * Colak * Ivica Arbanas

Sandor * Franjo Vodopija * Branko Borkovic

Plavsic * Petar Kacic * Juraj Njavro * Hosovci

Damjn Samardzic * Josip Tomasic * Velimir Djerek

Ivan Poljak * Andjelic * Jurkic * Kole Kovacic

Miroslav Sucic * Zdravko Radic * Brothers Molnar

|

| CAMPS |

Drvopromet * Nova Obucara *Borovo komerc * Luzac

Ruthenian Church * Aerodrom * Jews cementary

Police Department * Pizzeria Abazia * Eltz castle

New school * Recruitment office

Kindergarten Pcelica * Municipal basement |

| VICTIMS |

Jovan Jakovljevic * Radovan Stojsic * Ana Lukic

Mladen Mrkic * Vlado Skeledzija * Miroslav Radic

Stevan Inic * Darinka Grujic * Ljuban Vucinic

Zeljko Pajic * Milica Vracaric * Mirko Pojatic

Milenko Djuricic * Zoran Filipovic * Bosko Grbic

Ilija Lozancic * Stevo Malecki * Branko Mirjanic

Predrag Ciric * Sucevic * Ljubomir Bolic

Slavko Miodrag * Milan Vezmar * Marko Tolic

Sveto Nedeljkovic * Nedeljko Zunic

|

|

PUBLICAT.

|

Vuteks brand * Ovcara VS Dudik * Zvonko Ostojic

Milanovic and Plenkovic * Bloodsuckers of Sajmiste

Unspoken things * Autochauvinism * Terms confusion

Not admitting the crime * Vukovar through the centuries

Transcripts * Slavonian Napoleon

One-sided past * Hypocrisy in judgments

|

THE FUNERAL

Two days later, on July 1, 1991, family and friends set out by car to transport Jovan’s body to the Serbian village of Negoslavci, where the Jakovljević family grave is located.

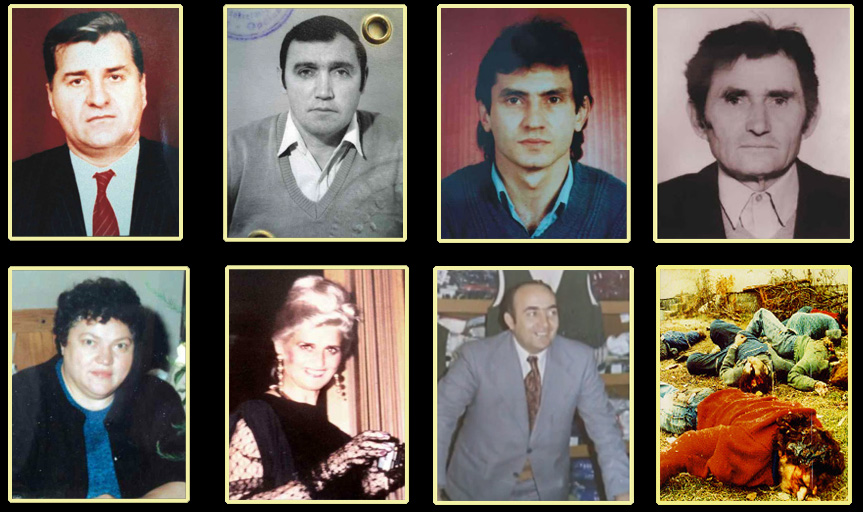

Some of Serb victims from Vukovar, 1991

They were stopped at the exit from Vukovar, where Croatian police officers demanded identification, documented their names, and subjected them to harassment. Among those accompanying Jovan on his final journey were also several Croats.

Jovan was one of many victims.

YEARS LATER

In the years following the murder, the family of the late Jovan Jakovljević repeatedly gave statements to the Croatian Ministry of the Interior and to the State Attorney’s Office of the Republic of Croatia, but the case has not advanced in any meaningful way.

It has long been known that the crime was committed by members of Merčep’s unit - commonly referred to as “Merčepovci” - who were armed and tasked with eliminating individuals on Merčep’s so-called blacklist.

To this day, no formal indictment exists in connection with Jovan’s murder. Only a generic report has been filed against an unidentified perpetrator. Together with other residents of Vukovar who lost family members at the hands of Croatian paramilitary forces in 1991, Jovan Jakovljević helped establish the association “Against Oblivion”, whose goal is to prompt the judiciary of the Republic of Croatia to initiate legal proceedings, bring the perpetrators to justice, and ensure they are appropriately punished.

Purveyors of False Promises: Tadic and Josipovic

When Croatian President Ivo Josipović and Serbian President Boris Tadić met in Vukovar in 2010, the association presented both leaders with the problems its members continued to face. Unfortunately, no steps were taken to assist those who had lost their loved ones.

This inaction was likely aimed at preventing the exposure of the chain of command and, by extension, avoiding acknowledgment of the ethnic cleansing of Serbs in Vukovar—a campaign carried out by Croatian civil, police, and paramilitary structures.

CONCLUSION

The case of Jovan Jakovljević is but one instance in a broader chain of crimes committed against Serbs in the Vukovar municipality in 1991. Similar unlawful acts occurred in other parts of the Socialist Republic of Croatia, including Zagreb, Split, Karlovac, Gospić, Sisak, Virovitica, Nova Gradiška, Osijek, Rijeka, Zadar, Šibenik, Ogulin, and beyond.

From the moment he assumed power in May 1990, Franjo Tuđman’s regime pursued the secession of Croatia from Yugoslavia, and the ensuing war served as a tool for the ethnic cleansing of Serbs from the newly proclaimed state. In this endeavor, Tuđman received substantial support from member states of the European Union and the NATO alliance, who throughout the 1990s consistently backed Croatia in the disintegration of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

For decades, the Croatian judicial system has systematically obstructed investigations and criminal proceedings in cases where the victims were of Serb ethnicity. Any convictions in such cases would significantly alter the dominant narrative of the so-called Homeland War (Domovinski rat) by demonstrating that Serbs, too, were victims, and that Croats were among the perpetrators of crimes.

Hate speech - Croats agaist cirilica

Given the widespread portrayal of Serbs throughout the Western world as the sole culprits for the breakup of Yugoslavia and the wars that followed, it is difficult to believe that anyone will ever be held accountable for heinous crimes such as the murder of Jovan Jakovljević, a Serbian civilian in Vukovar.

Tags:

Please, vote for this article:

Visited: 885 point

Number of votes: 0

|